What is “Gnostic”?

Most of the Gospels outside of the traditional New Testament are often called “Gnostic Gospels,” a term popularized by Elaine Pagels’ 1979 book of the same name. But does the term “Gnostic” clarify or actually complicate our understanding of these books? Many scholars now believe the term is not at all helpful. What does it even mean?

“Gnosticism” is a term used to categorize a “heresy” described by ancient “heresy hunters” (heresiologists) of the church, including Irenaeus, Hippolytus of Rome, Tertullian of Carthage, and Epiphanius of Salamis. Until the middle of the twentieth century, these “church fathers” remained the primary historical sources for this apparently loose collection of movements. This relatively recent term comes from the ancient label “Gnostic,” from the Greek word gnosis, which means “knowledge.” Irenaeus himself based his work on 1 Timothy 6:20, which warns against “the empty chatter and opposing ideas of so-called knowledge (gnoseos).” But although Irenaeus describes something “called Gnostic,” many scholars today question whether there ever was a specific movement or group of movements that could be summed up under the rubric of “Gnosticism.”

A Theory

Though the heresiologists spilled much ink describing what “Gnostics” believed, scholars building on their work tried to define ancient “Gnosticism” by summarizing key principles stemming from a dualistic view of spirit and matter – spirit being inherently good and matter being inherently evil. If God is spiritual (good), then who could have created a physical universe (evil)? Apparently, a “demiurge” or “craftsman,” a divine being lower than the true God. This “demiurge,” which was ignorant (at best) or evil (at worst), would then have enslaved good spirits in the prison of human bodies. How, then, could these good spirits escape their evil physical bodies and ascend to heaven? By receiving the teaching of the spiritual Christ, who could not have been truly human and so could not have died on the cross or risen from the dead, as traditional Christianity has maintained. The practical ramifications of these teachings, it was thought, led to one of two extremes: either an “ascetic” ethic that all material pleasure is also evil, or a “libertine” ethic that since matter is evil anyway, whatever spiritual people do in the flesh is irrelevant.

The Evidence

The discovery of the Nag Hammadi Library in Egypt in 1945 expanded the available source material for these movements. Scholars now had direct access to many of the texts these so-called “Gnostics” wrote and used. At first, they read these texts in light of what the heresiologists wrote. But more recently, some have questioned these traditional readings. The most notable include Karen King and Michael Williams (see below). They point out that the Nag Hammadi texts don’t all represent the same viewpoint, and furthermore that none of them individually contains all the ideas described above. Several don’t even contain any of these views. In short, many question that something called “Gnosticism” ever existed outside the creative imaginations of the heresiologists and church historians.

For more information, see my books The Gospel of Judas: The Sarcastic Gospel, pages 40-44, and The Gospel of Truth: The Mystical Gospel, pages 42-44. (This article is a revised excerpt from the latter.)

From Karen King

“[The Gospel of Truth], a writing from the mid-second century thought by many scholars to have been written by ‘the arch-heretic’ Valentinus himself, is an excellent example of a work that defies classification as a ‘Gnostic’ text. This remarkable work exhibits none of the typological traits of Gnosticism. That is, it draws no distinction between the true God and the creator, for the Father of Truth is the source of all that exists. It avows only one ultimate principle of existence, the Father of Truth, who encompasses everything that exists. The Christology is not docetic; Jesus appears as a historical figure who taught, suffered, and died. Nor do we find either a strictly ascetic or a strictly libertine ethic; rather, the text reveals a pragmatic morality of compassion and justice” (What Is Gnosticism?, p. 192).

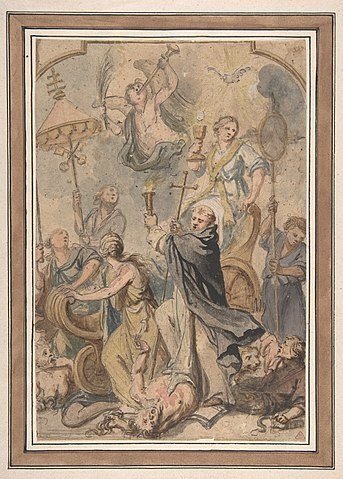

An Allegory of the Triumph over Heresy, with St. Domenic to the Fore, drawing, Abraham van Diepenbeeck (17th century).

Page 17 of The Gospel of Truth (NHC I,3).

For Further Reading

What Is Gnosticism? by Karen King is the most thoroughgoing deconstruction of the category of “Gnosticism.” Chapters include:

Why is Gnosticism So Hard to Define?

Gnosticism as Heresy

Adolf von Harnack and the Essence of Christianity

The History of Religions School

Gnosticism Reconsidered

After Nag Hammadi I: Categories and Origins

After Nag Hammadi II: Typology

The End of Gnosticism?

Rethinking “Gnosticism”: An Argument for Dismantling a Dubious Category by Michael Allen Williams is a systematic and meticulous study. Chapters include:

What Kind of Thing Do Scholars Mean by “Gnosticism”?

“Gnosticism” as a Category

Protest Exegesis? or Hermeneutical Problem-Solving?

Parasites? or Innovators?

Anti-Cosmic World Rejection? or Sociocultural Accommodation?

Hatred of the Body? or the Perfection of the Human?

Asceticism …?

… or Libertinism?

Deterministic Elitism? or Inclusive Theories of Conversion?

Where They Came From …

And What They Left Behind