Scripture vs. Canon

Why should we talk about Gospels outside of the traditional Christian Bible? Aren’t the New Testament’s four Gospels enough? Why remake the Bible, which has already withstood the test of time? Aren’t these other Gospels heretical? After all, the most prolific writer of the New Testament, Paul, warned against “turning to a different gospel” (Gal. 1:6). Don’t these other Gospels contradict the Bible? Finally, doesn’t the Book of Revelation warn against adding to – or subtracting from – the Bible?

Some of these questions actually stem from a misunderstanding of the Bible’s teaching. For example, Revelation 22:18, 19 doesn’t actually warn against adding to or subtracting from the New Testament, which had not yet been finalized at that point. And in his letter to the Galatians, Paul wasn’t addressing written Gospels – after all, none of them had actually been written yet. Nor do all of those other Gospels necessarily “contradict” the New Testament’s Gospels – at least no more than the New Testament Gospels contradict one another. Then again, “contradictory” is probably not the best way to describe the differences between the Gospels. It’s probably more helpful simply to affirm that various Gospels, written by various followers of Jesus and their communities, reflected different concerns in the way they wrote their stories. See my book The Gospel of Thomas: A New Translation for Spiritual Seekers, pp. 13-15.

The Canon

The remaining questions above are more involved, however. They’re questions about the “canon” or “rule” of the Bible – specifically, which books are included and which books aren’t. As I’ve written elsewhere, those questions are inseparable from questions about institutional authority in the church. Traditionally, many Christians have defined Christianity in terms of three Cs: creed, canon, and clergy, with each mutually reinforcing the other. Organized churches generally seek consistency between their beliefs (creed), their authoritative texts (canon), and their designated authorities (clergy). Canonical texts (as defined by the clergy) are consistent with the church’s creed; the church’s creed in turn is based on its canon; and its clergy, authorized by its canons, maintain the accuracy of its creed. In other words, the authority of the three Cs is self-referential. (Which is why I advocate defining Christian churches by means of a different three Cs: “Christ-centered communities,” irrespective of the other three Cs.)

So to ask whether the “canon” of scripture needs to be changed is to ask what changes different institutions are inclined to make. Different institutional churches already have different canons (along with different creeds and different opinions about clergy). The Catholic canon is larger than the Protestant canon, and the Orthodox canon is larger than the Catholic canon. What one church considers “apocrypha,” another considers part of their Bible. Canons of Scripture, then, are defined by the institutions that use them. Enlarging or restricting their canons is up to them.

Extracanonical Scriptures

At the same time, however, there’s immense benefit to savoring early Gospels that weren’t ultimately included in the New Testament canon. I also consider them Scriptural texts, and find them to be just as inspiring and thoughtful as the New Testament’s four Gospels. In some cases, I find them to be more inspiring (like The Gospel of Mary); in others, I find them less so (like The Gospel of Judas). Others will have different reactions and experiences entirely, which is as it should be. People are different, and their needs aren’t always the same. Not everyone is at the same point in their spiritual journey.

How can these two ideas be held in tension – that other Gospels can be Scripture without being part of the New Testament’s canon? Here it’s helpful to consider the difference between Scripture and canon. They overlap, clearly, because biblical canons preserve communities’ sacred scriptures. But Scriptures (i.e., sacred writings) don’t need to be canonical to be read and cherished. As the idea of a canon slowly emerged in the early church, Jesus’ followers understood this well.

The Muratorian Fragment

For example, an early document known as the Muratorian fragment addresses questions about which books should be included in the Christian canon. When it comes to a popular second-century book named the Shepherd of Hermas, the Muratorian fragment states that it “ought to be read,” but goes on to state that “it cannot be made public in the church to the people, nor placed among the prophets, as their number is complete, nor among the apostles to the end of time.” So the author didn’t think the Shepherd of Hermas should be publicly read in church, although it was still valuable and “ought to be read” privately. It wasn’t to be included in the liturgy, but that didn’t mean it was to be shunned.

On the other hand, the Muratorian fragment goes on to argue that some books should be “rejected” entirely, including the writings of Valentinus (which would likely exclude The Gospel of Truth). This does reflect the reality that early followers of Jesus debated which texts to use. But what the Muratorian fragment also shows is that the canon was fluid in the first few centuries, and that some extracanonical books should still be read. That’s something I can agree with.

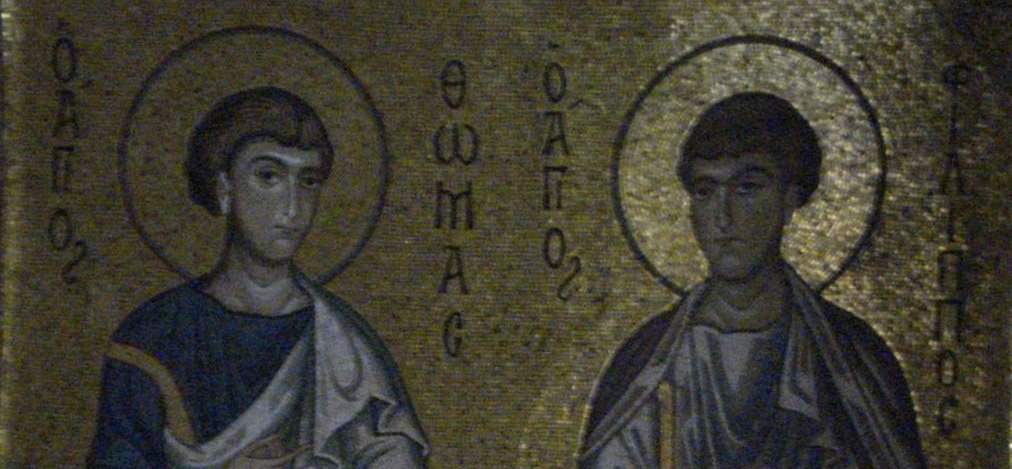

Above: The Apostle Thomas and the Apostle Philip (La Martorana Church).

The Gospel of Thomas and The Gospel of Philip were both included in Nag Hammadi Codex II, discovered in Egypt in 1945.